Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: National Cancer Data Base analysis of a gender-specific carcinoma with good prognosis

Introduction

Solid pseudopapillary tumor (SPT) of the pancreas is a rare clinical entity recognized as an indolent pancreatic tumor with potential malignant behavior in the past years. It represents 1–3% of all pancreatic tumors and 10–15% of cystic tumors of the pancreas (1,2). It occurs predominantly in adolescent girls and young women; comparatively, much rare in men (3-5). Although previously believed to be mostly benign, around 15% of resected cases have shown malignant features and are subsequently categorized as solid pseudopapillary carcinoma (SPC) (2,6-8). More recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) has reclassified all solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPNs) as low-grade malignant neoplasms as our understanding of the histology and prognosis increases (9). Although most patients with SPNs have a favorable prognosis after radical resection, local recurrence or metastasis can occur after surgery (7,10,11). While there are multiple reports of SPNs that have been published in recent years, the majority of these studies are single-center reports or small case series. This striking gender distribution and lack of data using large series of patients has led us to undertake further study of this rare disease. In this study, we use the cohort from National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) and construct a comparative analysis by gender on the clinicopathological features, surgical treatments, and the long-term outcomes of SPNs.

Methods

Database and patient population

The NCDB is a joint project of the Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society, which captures approximately 70% of all newly diagnosed cases of cancer in the United States (12). With approval of the institutional review board, we identified patients with pancreatic SPN (code 8452/3) between 1998 and 2012 from the NCDB, with PUF dictionary version 2014 used for definitions.

Demographic and clinicopathological data were extracted and recoded according to the grouping protocol. We defined surgical resection to be a pancreatic resection aimed at removal of the primary tumor, including partial or distal pancreatectomy coded by 25, 30, 80 and 90, pancreatoduodenectomy coded by 35, 36, 37 and 70, and total pancreatectomy coded by 40 and 60. Ethnicity codes were used to group the race into Caucasian (code 01), African American (code 02) and other. For the primary tumor location, we combined the body and tail together, with unclear and not otherwise specified locations being defined as other. Analytic stage grouping was used and collapsed into the corresponding general stage designation according to AJCC clinical and pathologic stage. Charlson-Deyo score was recorded as an estimate of patient comorbidity. Other clinicopathological factors included patient's age, gender, tumor size, tumor grade, surgical margin, lymph vascular invasion, number of examined and positive lymph nodes, chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data were analyzed using the chi-square test, and quantitative variables were compared using the independent samples t test. Survival function estimation and comparison were performed using Kaplan–Meier estimates and the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model were used to evaluate the hazard ratio (HR) and the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the possible prognostic factors. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS v.22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All statistical tests were two-sided, with alpha equal to 0.05.

Results

Clinicopathological characteristics

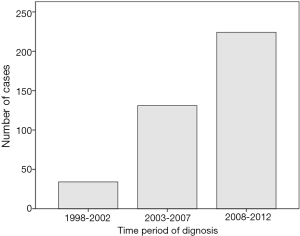

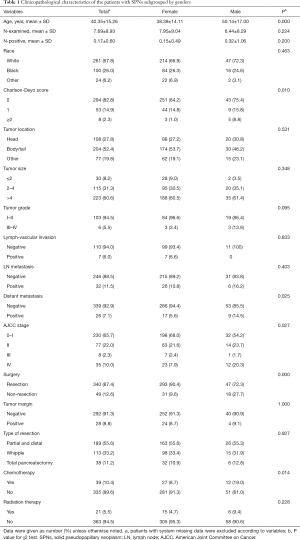

Between January 1998 and December 2012, a total of 356,108 patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer were registered in the NCDB, consisted of 389 (0.1%) cases categorized for pathologically confirmed malignant SPN. The number of patients with SPN has continued to increase during the last 15 years (34 for 1998–2002, 131 for 2003–2007 and 224 cases for 2008–2012), a majority of which were female (324/389, 83.3%) (Figure 1). Only three patients were registered in the first 3 years, while 146 patients were registered during the last 3 years. Male patients were diagnosed at significantly older age than female patients (mean age: 50.1 vs. 38.4 years, P<0.0001), more likely to have distant metastasis (14.5% vs. 5.6%, P=0.03), less likely to undergo surgical resection (72.3% vs. 90.4%, P<0.0001), and more likely to receive chemotherapy (19.0% vs. 8.7%, P=0.01). Other clinicopathological features of the patients were listed with comparison in Table 1.

Full table

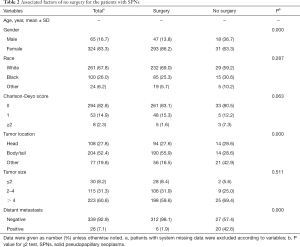

Reasons for non-operative management

There were 49 patients that did not undergo surgical resection. The majority of this cohort was not recommended surgery as part of the planned first course treatment based on the oncologic baseline evaluation (40/49). Two patients were not recommended surgery due to patient risk factors, and four patients were recommended surgery but did not pursue surgery due to other factors. Compared with the patients who underwent surgery, patients without surgery were more likely to be diagnosed at an older age (mean age: 52.0 vs. 38.7 years, P<0.0001), to have uncertain tumor sites of pancreas (42.9% vs. 16.5%, P<0.0001), and to have distant metastasis (42.6% vs. 1.9%, P<0.0001). Other factors, such as tumor size and comorbidity, had no significant differences between the two groups (Table 2).

Full table

Survival outcomes

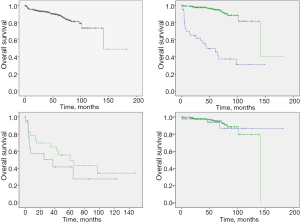

Patients with SPNs had a mean survival time (139.8±9.4 months), with an impressive 5-year and 10-year overall survival (89.0% and 73.7%). Patients who did not undergo surgery had significantly worse survival when compared with the surgical group (5-year survival: 49.7% vs. 95.0%, P<0.001). Among 49 patients who did not undergo surgery, male patients appear to have worse survival than female patients (median survival: 37.4 vs. 60.5 months, P=0.33). For surgical patients, there is no survival difference between sex groups (5-year survival: 94.0% vs. 95.2%, P=0.86) (Figure 2).

Discussion

SPN was first described and misdiagnosed with nonfunctioning islet cell tumors, named as Frantz’s tumors in 1959 (13). Since then, these tumors have been recognized as rare and usually benign neoplasms with predominant manifestation in young women, named as several synonyms no longer used, including solid-pseudopapillary tumor, solid-cystic tumor, papillary-cystic tumor, and solid and papillary epithelial neoplasm (2,14). During that period, criteria of malignancy had not been clearly established. Generally, SPN was defined as malignant when there was evidence of unequivocal extra-pancreatic invasion, pancreatic parenchymal invasion, perineural invasion, vascular invasion, and distant metastases (3,15-17). Meanwhile, distant metastasis could also occur in the patients with bland-looking SPN when the other above-mentioned histological criteria of malignancy were not detected (1,18), and no significant influence of vascular or peripancreatic tissue invasion was noted (19). Due to the controversial indications of malignancy, benign appearing solid-pseudopapillary neoplasms were later classified as lesions of uncertain malignant potential according to WHO᾿s suggestion in 2000 (15), and then again reclassified all of the SPNs as low-grade malignant neoplasms with the category for benign behavior removed in 2010 (9).

While Many investigator have tried to review SPNs in a large series (6,20-27), there are only nine reports published in English with a study cohort over 50 patients in the last 20 years; the largest of which included 187 patients from Peking Union Medical College Hospital in China (27). Given the new standard of WHO classification and progress in imaging techniques, the number of registered SPNs in NCDB data base should likely have a similar increase in the number of SPNs detected. However, only 389 patients with SPNs were enrolled in the data base, accounted for 0.1% of the total population with pancreatic tumors, which was lower than the previously reported ratio. Nevertheless, while this data from NCDB was likely incomplete, this study has still contributed the largest retrospective cohort for SPN research until now. In addition, detailed guidelines for clinical practice and enrollment still need to be revised for the future analytic research.

Generally, the majority of the SPNs occur in the young female population, with a wide age range as 2–85 years old (1,2). Differing from previously described reports (1-5), data from our study showed that the average age of the SPN patients was older; 38.4 years old for female, and 50.1 years old for male, with a male/female ratio of approximately 1:5. Lam et al. conducted a total of 452 cases from literature including 189 occurrences in Asian and 59 occurrences in African American populations, as well as demonstrating that SPNs in Japan tended to be found in older patients and were more frequent among men than usual (28). It seems that the striking sex and age distribution should be related to genetic and hormonal factors, but there are no reports indicating an association with endocrine disturbances such as overproduction of estrogen or progesterone in the past decades. Typical SPN is composed of poorly cohesive, monomorphic cells forming solid and pseudopapillary structures with fibrovascular stalks, frequently showing hemorrhagic-cystic degeneration and variably expressing epithelial, mesenchymal and endocrine markers (9). Basically, no significant difference was observed between male and female SPNs in regards to tumor characteristics of size, macroscopic cystic degeneration, necrosis, lymphovascular involvement, perineural invasion, capillary density, and immunohistochemical expression of known markers (10,29,30). In contrast, SPN in men tends to exhibit solid components that lack prominent pseudopapillary or pseudoglandular formations and prominent degenerative changes (29).

Based on limited data, the phenomenon for atypically aggressive behavior of SPNs in males is lacking in explanation. Our analysis shows that male patients with SPNs were diagnosed at significantly older age than female patients and more likely to have distant metastasis, resulting in them being less likely to undergo surgical resection and to have worse prognosis, which is similar data reported in previous studies (10,31). We also found there was no survival difference between genders when both underwent surgical resection. Valid prognostic factors are still lacking due to insufficient data for analysis in this study. Given that the reasons for more aggressive behavior and worse survival in male patients remains unclear, male patients with SPNs should be recommended to be treated by a more radical resection and to be observed closely during follow-up.

In conclusion, SPN is a rare pancreatic neoplasm that occurs predominantly in young females. Surgical resection conveys a significant survival advantage and should be pursued whenever possible. When SPN does occur in males, it tends to be diagnosed at a much later age and is more likely to have distant metastasis. This leads to a significant difference in survival between genders with SPN that is not seen when surgical resection is undertaken. More research is needed to understand the differences between men and women diagnosed with this rare pancreatic tumor.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: This type of study is waived from IRB review at Baptist MD Anderson Cancer Center.

References

- Law JK, Ahmed A, Singh VK, et al. A systematic review of solid-pseudopapillary neoplasms: are these rare lesions? Pancreas 2014;43:331-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Papavramidis T, Papavramidis S. Solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: review of 718 patients reported in English literature. J Am Coll Surg 2005;200:965-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goh BK, Tan YM, Cheow PC, et al. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas: an updated experience. J Surg Oncol 2007;95:640-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang F, Jin C, Long J, et al. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: a case series of 26 consecutive patients. Am J Surg 2009;198:210-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stark A, Donahue TR, Reber HA, et al. Pancreatic Cyst disease: a review. JAMA 2016;315:1882-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee SE, Jang JY, Hwang DW, et al. Clinical features and outcome of solid pseudopapillary neoplasm: differences between adults and children. Arch Surg 2008;143:1218-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim MJ, Choi DW, Choi SH, et al. Surgical treatment of solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas and risk factors for malignancy. Br J Surg 2014;101:1266-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu P, Cheng X, Du Y, et al. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas: a 19-year multicenter experience in China. J Gastrointest Surg 2015;19:1433-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System, Fourth Edition. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Press; 2010:279-337.

- Machado MC, Machado MA, Bacchella T, et al. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: distinct patterns of onset, diagnosis, and prognosis for male versus female patients. Surgery 2008;143:29-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang F, Fu DL, Jin C, et al. Clinical experiences of solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas in China. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;23:1847-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lerro CC, Robbins AS, Phillips JL, et al. Comparison of cases captured in the national cancer data base with those in population-based central cancer registries. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:1759-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Franz VK. Papillary tumors of the pancreas: benign or malignant? In: Franz VK, editor. Tumors of the Pancreas. Atlas of Tumor Pathology. Washington, DC: US Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1959: 32-3.

- Madan AK, Weldon CB, Long WP, et al. Solid and papillary epithelial neoplasm of the pancreas. J Surg Oncol 2004;85:193-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hamilton SR AL, editors. WHO classification of tumors. Pathology and genetics of tumours of digestive system. Lyon, France: IARC Press 2000:p. 204.

- Marchegiani G, Andrianello S, Massignani M, et al. Solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: Specific pathological features predict the likelihood of postoperative recurrence. J Surg Oncol 2016;114:597-601. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim JH, Lee JM. Clinicopathologic review of 31 cases of solid pseudopapillary pancreatic tumors: can we use the scoring system of microscopic features for suggesting clinically malignant potential? Am Surg 2016;82:308-13. [PubMed]

- Lee HS, Kim HK, Shin BK, et al. A rare case of recurrent metastatic solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas. J Pathol Transl Med 2017;51:87-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Irtan S, Galmiche-Rolland L, Elie C, et al. Recurrence of solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas: results of a nationwide study of risk factors and treatment modalities. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2016;63:1515-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang X, Zhang J, Che X, et al. Peripancreatic lymphadenopathy on preoperative radiologic images predicts malignancy in pancreatic solid pseudopapillary neoplasm. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015;8:16315-21. [PubMed]

- Li G, Baek NH, Yoo K, et al. Surgical outcomes for solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas. Hepatogastroenterology 2014;61:1780-4. [PubMed]

- Estrella JS, Li L, Rashid A, et al. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: clinicopathologic and survival analyses of 64 cases from a single institution. Am J Surg Pathol 2014;38:147-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cai Y, Ran X, Xie S, et al. Surgical management and long-term follow-up of solid pseudopapillary tumor of pancreas: a large series from a single institution. J Gastrointest Surg 2014;18:935-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang LJ, Bai L, Su D, et al. Retrospective analysis of 102 cases of solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas in China. J Int Med Res 2013;41:1266-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ye J, Ma M, Cheng D, et al. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: clinical features, pathological characteristics, and origin. J Surg Oncol 2012;106:728-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim CW, Han DJ, Kim J, et al. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: can malignancy be predicted? Surgery 2011;149:625-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang WB, Zhang TP, Sun MQ, et al. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas with liver metastasis: Clinical features and management. Eur J Surg Oncol 2014;40:1572-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lam KY, Lo CY, Fan ST. Pancreatic solid-cystic-papillary tumor: clinicopathologic features in eight patients from Hong Kong and review of the literature. World J Surg 1999;23:1045-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takahashi Y, Hiraoka N, Onozato K, et al. Solid-pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas in men and women: do they differ? Virchows Arch 2006;448:561-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tien YW, Ser KH, Hu RH, et al. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas: is there a pathologic basis for the observed gender differences in incidence? Surgery 2005;137:591-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin MY, Stabile BE. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: a rare and atypically aggressive disease among male patients. Am Surg 2010;76:1075-8. [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Wang X, Sich N, Wang J, Heuthorst L, Pezzi C. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: National Cancer Data Base analysis of a gender-specific carcinoma with good prognosis. Art Surg 2017;1:3.